8 Col di Prà (843 m a.s.l.) - The North Edge of Agnèr

"... the grandiose architecture of the Dolomites surges with terrible force - looking form the bottom of the valley, one has to twist one's head upwards in order to take it all in. Monte Agnèr looms with its peak of a kilometre and a half; in front and beyond the more modest but by no means less charming stream are the walls of Pale di San Lucano. Less than 2900 metres high, the peak itself doesn't amount to much in terms of height. But what other Alpine cathedral can boast such apse? When it blazes in the setting sun and the pale clouds begin to engulf it slowly, one is charmed into believing that such sight could not possibly exist."

Dino Buzzati, Cordata di tre (A Roped Team of Three), in “Corriere della Sera”, June 23, 1956.

The North Edge of Agnèr

With a height of 1550 metres, Monte Agnèr's North Edge is part of the mountain walls which made history in mountain climbing and competes with Eiger's North Face for the title of the highest wall in the Alps.

Let us now go on to explore and find out how such a structure could have formed right here. The tilted, almost vertical rocky walls are formed solely of rocks that are resistant to erosion - hard, compact and tough. Vertical walls several hundred metres high could be quite common, their number diminishes, whoever as they continue to grow in height. In order to become gigantic, however, the resistant rocks should have the necessary thickness as well.

The Valley of San Lucano was dug in the core of the reef that is now the Pale di San Martino, Pale di San Lucano and the Civetta Group, and, compared to the other valleys, it reveals unique geological past.

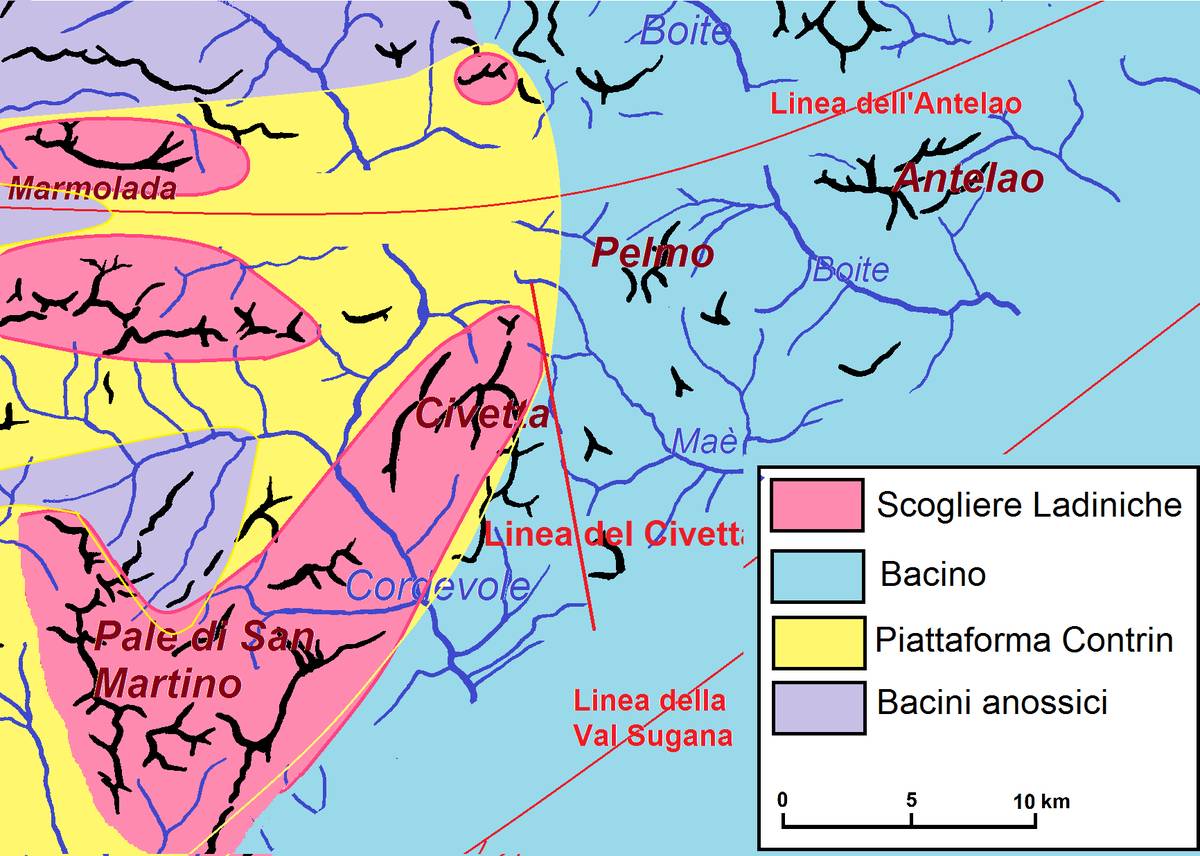

Towards the end of the Anisian (243 million years ago), the Dolomites were divided in two by a straight fault line, situated to the east of Mount Civetta; to the west there was a vast basin area and a carbonate platform, crisscrossed by straight basin zones, dominated the area to the west. The whole area was subject to sinking (subsidence). The deepening of the seabed wasn’t the same everywhere - while in the neighbouring areas there was an accumulation of several dozens of metres of platform limestones (Contrin Formation), the area around Agnèr, Pale di San Lucano, and the Civetta was affected by a much more rapid sinking, where more than half a kilometre of massively stratified limestone and dolomites were accumulated. The sudden rise in the sea level called transgression created open sea conditions throughout the entire region. Some communities of calcium carbonate-fixing organisms emerged on the platform's more shallow areas; these consisted mainly of bacteria but there were also algae, sponges and corals. The subsidence rate was quite high, however, the new platform grew at the same rate as the deepening, thus providing a high-rate carbonate production. During this initial period the vertical growth called aggradation clearly prevailed over the horizontal growth known as progradation. The numerous original nuclei melted into a single structure, which, in the course of three to four millions years, reached a thickness of more than a thousand metres - significantly higher than other reefs in the Dolomites.

In conclusion, the thick pile of hard rocks which sculpted Agnèr's North Edge is the product of the high rate of subsidence that impacted this specific area of the Dolomites between the end of the Aninsian and the beginning of the Ladinian.

Reproduction of the paleogeographic structure of the Dolomites at the end of the Anisian. The Civetta line separates the high structural zone in the west where the Contrin Formation initially settled and then the Schlern Formation from the lower area in the east where basin formations are deposited (ill. DG).

Reproduction of the paleogeographic structure of the Dolomites at the end of the Anisian. The Civetta line separates the high structural zone in the west where the Contrin Formation initially settled and then the Schlern Formation from the lower area in the east where basin formations are deposited (ill. DG).

A view from Col di Prà towards Agnèr; from left to right: Spiz Piciol, Spiz d'Agnèr Nord and Spiz d'Agnèr Sud, Agnèr, Torre Armena and Lastei d'Agnèr. Upfront on the right is Col Negro. Monte Agnèr's huge pillar is separated from Spiz and Torre Armena by two vertical transcurrent faults which facilitated the selective erosion processes. The tiny hanging glacial cirque of Van de Mez where Bivacco Cozzolino is located is to the left of the Edge (photo DG).

A view from Col di Prà towards Agnèr; from left to right: Spiz Piciol, Spiz d'Agnèr Nord and Spiz d'Agnèr Sud, Agnèr, Torre Armena and Lastei d'Agnèr. Upfront on the right is Col Negro. Monte Agnèr's huge pillar is separated from Spiz and Torre Armena by two vertical transcurrent faults which facilitated the selective erosion processes. The tiny hanging glacial cirque of Van de Mez where Bivacco Cozzolino is located is to the left of the Edge (photo DG).

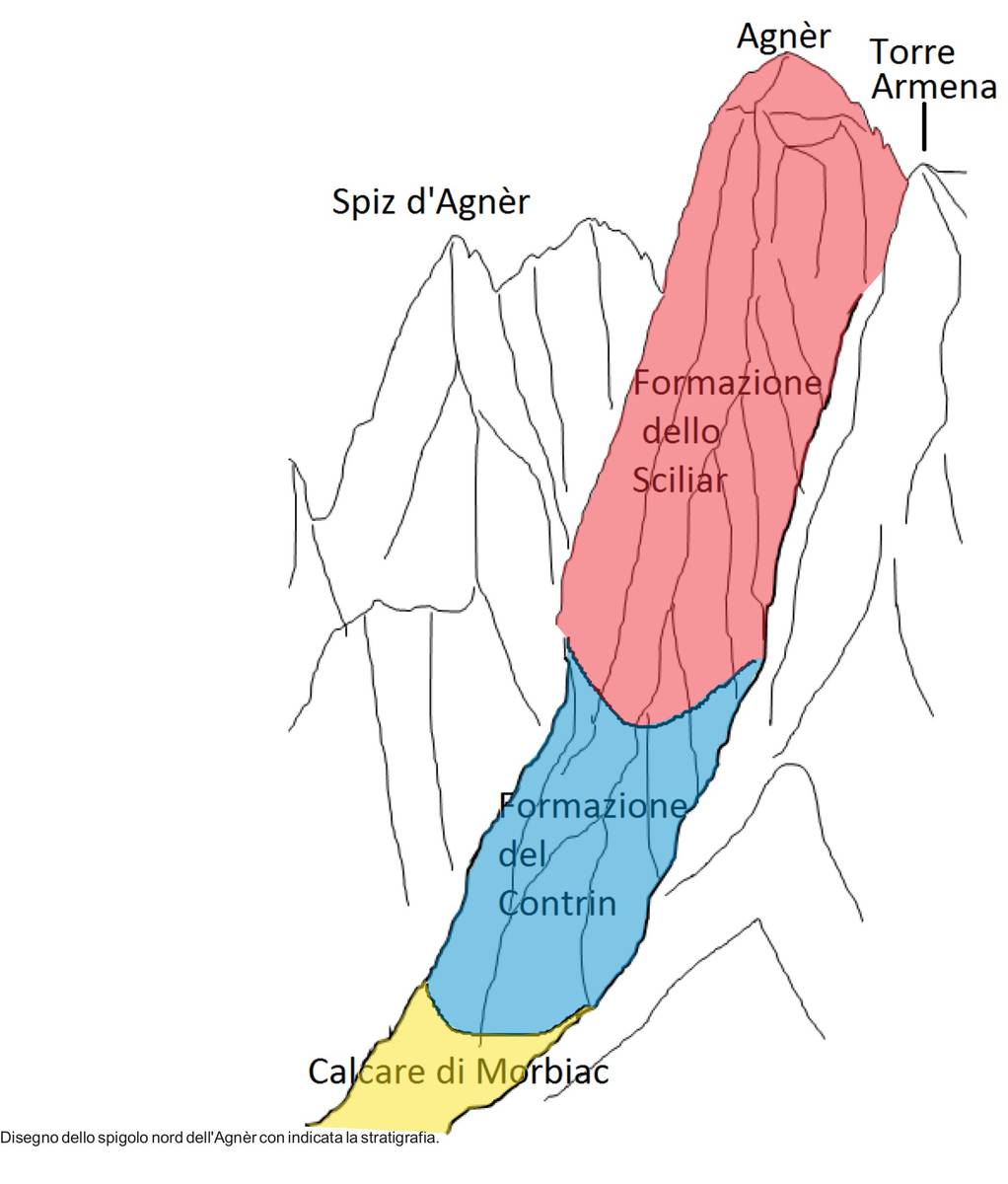

Geological sketch of Monte Agnèr (ill. DG).

Geological sketch of Monte Agnèr (ill. DG).

The Piz Landslide

The San Lucano valley features enormous differences in height and has thus been affected by landslides since its very origin. The remains of ancient landslides originating immediately after the retreat of the glaciers, are largely buried under recent or current alluvial and detrital deposits. There is, however, an imposing landslide deposit at the base of Pale dei Balconi (Monte Piz) which has the characteristics of a deep-seated gravitational slope deformation (DSGSD). The volume of this enormous mass is estimated to be 100 million cubic metres and of compact appearance and borders strips of fractured rocks. The mass is off axis with respect to the original U-shaped conformation of the valley and framed upwards by a semicircular niche.

DSGSDs generally evolve over a long period of time affecting entire slopes with dimensions that can reach one billion cubic meters. They have no specific movement surface, but rather feature a deformation by micro-fracturing within a more or less wide band of the rock mass. The deformation phase is very long, which could evolve into a paroxysmal phase.

DSGSDs are movements that tend to balance such slopes that are not in equilibrium for various reasons. A predisposing factor is the existence of a structural weakness of the rock, which could be either intrinsic and on a small scale, such as schistosity and cohesive weakness, or a medium-structural, namely inherent to the local and regional geotectonic history, such as the existence of fracturing systems and faults. This phenomenon is called deformation and can be further classified as dipping. Generally speaking, and in the low-middle range in particular, no real cutting plane can be identified. The latter is limited to the upper part of the areas impacted by deformation which is highlighted by a series of cuts aligned transversely to the line of slope (surfacing of movement planes). There occurs a "swelling" of sorts in the lower-middle part of the slope towards the exterior occurs in order to compensate the downward thrust of the top parts. A frequent result is a new real landslide detaching from the lower part because of lack of balance.

The image taken from Livinàl Lonc (right side of the Val d 'Angeràz) helps us identify an anomalous structure shifted forward in relation to the side of the valley and located at a lower position compared to the hill above. It represents the landslide structure of a DSGSD. The clear detrital ravine of Val della Civetta is developed along the limit of the landslide body (photo DG).

The image taken from Livinàl Lonc (right side of the Val d 'Angeràz) helps us identify an anomalous structure shifted forward in relation to the side of the valley and located at a lower position compared to the hill above. It represents the landslide structure of a DSGSD. The clear detrital ravine of Val della Civetta is developed along the limit of the landslide body (photo DG).

The hamlet of Col di Prà

Unlike Villanova or Forno di Val, the hamlet of Col di Prà boasts houses with colourful walls, built with a remarkable variety of rocks. Apart from the light-coloured dolomite, there are the reddish sandstone blocks of the Werfen Formation and the Voltago Conglomerate. Other identifiable stones are dark magmatic rocks (andesites, monzonites, pyroxenites) and black bituminous limestones bearing witness to the geological complexity of the Valley.

Because of the storm Vaia on the 29th of October 2018, Col di Prà has recently been covered by alluvial debris as the river Rio Bordina practically tore a bridge and gouged a wide ravine at the confluence with Tegnàs. Similar phenomena of even greater magnitude have also occurred in the past.

In the 1700s Col di Prà was the home of farmers, miners and blacksmiths. According to the witness accounts of Giuseppe Alvisi: Belluno and its Province from 1859, the iron mines located on Col de la Vena and on Stia de Val de Gardès supplied siderite, or iron carbonate, which was then processed in the small smelting furnaces and worked in the forges belonging to the Crotta family in Col di Prà. Analyses of the local geology and the depots lead us to believe that the mines were actually located not far from the stream Bordina under Pian della Vena and at the base of Lastia di Gardès.

According to Alvisi, following intense and prolonged rains in the autumn of 1748, a landslide broke off the north-eastern side of Monte Piz, obstructing the flow of the Bordina stream; the detachment niche is still easily recognisable nowadays. A temporary lake was created and filled immediately by the waters coming from the large hydrographic basin of the stream Bordina. The barrier suddenly collapsed as a staggering amount of water and debris hit the village, devastating the countryside and several houses and destroyed the factories which had been built near the stream out of necessity. It was precisely because of this event that the village of Prà was built in a location protected from the stream, but as we have seen, not from landslides.

Download

|

Download the full content of the information panel number 8 (pdf format) |